The reports of blueberry gall midge infestations in Georgia blueberries have become more common over the last couple of years. Blueberry gall midge, Dasineura oxycoccana (Johnson) (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae) was first identified as a pest of rabbiteye blueberries in the southeastern United States in early 1990s. Since then, gall midge has been confirmed as a pest of blueberries in major blueberry-growing states throughout the United States. The gall midge larvae feed on developing floral and vegetative buds in southern highbush and rabbiteye blueberries. The infested buds appear dry and shriveled, and eventually disintegrate. Severe gall midge infestations can cause up to 80% crop loss if appropriate control measures are not implemented in a timely manner.

Adults are very small and fragile flies, approximately 2-3 mm long (Fig. 1a). Adult flies have long slender legs, globular cylindrical antennae, and transparent wings with long black hair-like structures and reduced venation. Females lay eggs in floral or vegetative buds just after bud swell, as soon as scales of flower buds begin to separate and the tips of flowers become visible. Totally dormant buds are not infested. The adult stage probably lasts only for a few days (less than a week) during which time a single female can lay up to 20 eggs. Eggs hatch in 2-3 days. First instar larvae are less than 1 mm long, white and almost transparent. They then go through three instars and develop into mature larvae in about 7-10 days (Fig. 1b). The full-grown larvae are about 1mm long, 0.3 mm wide, legless, and reddish-orange in color. Once fully fed, the larvae cease feeding, come out of the buds and drop to the ground to pupate in soil. The puparia transform into adult flies in a few days. In South Georgia, gall midges can complete 5-6 generations from January through June.

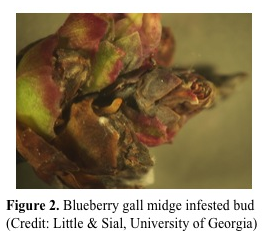

Earlier in the season, midge larvae feed on floral bud tissues and on the pedicels that hold the individual flower buds to the peduncle within the developing flower cluster. As a result, flower buds dry up and disintegrate within about two weeks after infestation (Fig. 2). Depending on severity of infestation, high levels of flower bud abortion (as high as 80%) may occur. Although both rabbiteye and southern highbush blueberries are susceptible to blueberry gall midge, the impact of gall midge infestation is relatively less on early blooming cultivars of southern highbush because of the earlier timing of floral bud development. Later in the season, as plants progress to vegetative budding, oviposition also occurs on the new shoot meristems. Infested vegetative buds swell and the outer leaves curl enfolding feeding larvae inside. Vegetative meristems may also be infested and killed leading to distorted and blackened shoot tips, characteristic symptoms of damage caused by gall midge. The damage caused by gall midge in blueberries might be confused with frost damage or boron deficiency. The severity of damage depends on temperature and other climatic factors, and generally tends to be worse after mild winters.

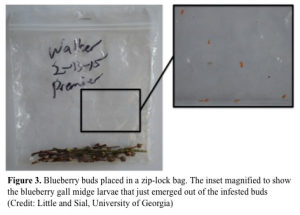

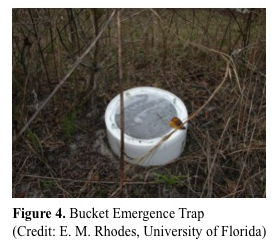

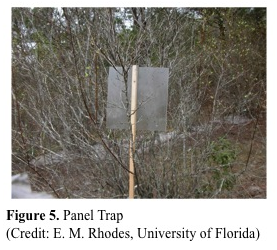

The small size of the blueberry gall midge larvae and adult flies, and the larval feeding occurring inside the buds makes field detection very difficult before damage occurs. However, blueberry gall midge infestations can be detected prior to the onset of symptoms by collecting bud samples and using emergence traps and panel traps. For bud sampling, collect five young buds from 10-15 randomly selected bushes per acre. Place the buds into a zip-lock bag at room temperature. If buds are infested, reddish-orange larvae will begin to emerge after 3-4 days (Fig. 3). The emergence traps made up of an overturned bucket with a sticky transparent window at the top (Fig. 4) can be used to detect gall midge populations earlier in the season. These traps can also be used to predict peaks in larval infestation which is important for targeting pesticide application. Panel traps consisting of 1ft x 1 ft sticky panel attached to a metal or wooden post (Fig. 5) can also be used to detect midge adults.

The blueberry gall midge larvae are very difficult to kill using insecticides because they are protected by surrounding plant tissue while feeding inside the buds. It is therefore extremely important to kill adults before they lay eggs in the buds. However, because of their ability to go through multiple generations per season and short adult lifespan, careful scouting and timing of insecticide application are key to successful control of blueberry gall midge. Insecticides that have been shown to be effective against blueberry gall midge include Diazinon, Delegate, Imidan, Malathion, and Assail. Entrust is the only effectives material for certified organic blueberries. For specific insecticide recommendations, please refer to Southeast Regional Blueberry Integrated Management Guides available at https://www.smallfruits.org/SmallFruitsRegGuide/index.htm. Several species of endoparasites such as Synopeas spp., Platygaster spp., and Inostemma spp. have been reported to contribute significantly to the biological control of blueberry gall midge populations, but the actual impact will depend on populations densities of these natural enemies in the blueberry orchards.

References:

- Gagne, R. J. 1989. The Plant-feeding Gall Midges of North America. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY 356 pp.

- Liburd, O. E., E. M. Sarzynski, N. Benda, E. M. Rhodes, B. J. Sampson. 2013. Blueberry gall midge: a major insect pest of blueberries in the southeastern United States. University of Florida, IFAS Extension Publication ENY825.

- Lyrene, P. M. and J. A. Payne. 1993. Blueberry gall midge: A pest in rabbiteye blueberry in Florida. Proceedings, Florida State Horticulture Society, 105: 297-300.

- Lyrene, P. M. and J. A. Payne. 1995. Blueberry gall midge: A new pest of rabbiteye blueberries. Journal of Small Fruit and Viticulture 3: 111-124.

- Sampson, B. J., S. J. Stringer, and J. M. Spiers. 2002. Integrated pest management for Dasineura oxycoccana (Diptera: Cecidomyiidae) in blueberry. Environmental Entomology 31: 339-347.

- Yang, W. Q. 2005. Blueberry gall midge, a possible new pest in the Northwest: Identification, life cycle, and plant injury. Oregon State University, Extension Service Publication EM8889.