Authors: Dr. Zilfina Rubio Ames, Assistant Professor and Small Fruit Extension Specialist, University of Georgia, Tifton Campus; Dr. Jonathan E. Oliver, Associate Professor and Fruit Pathologist, University of Georgia, Tifton Campus

Background and Recent Observations

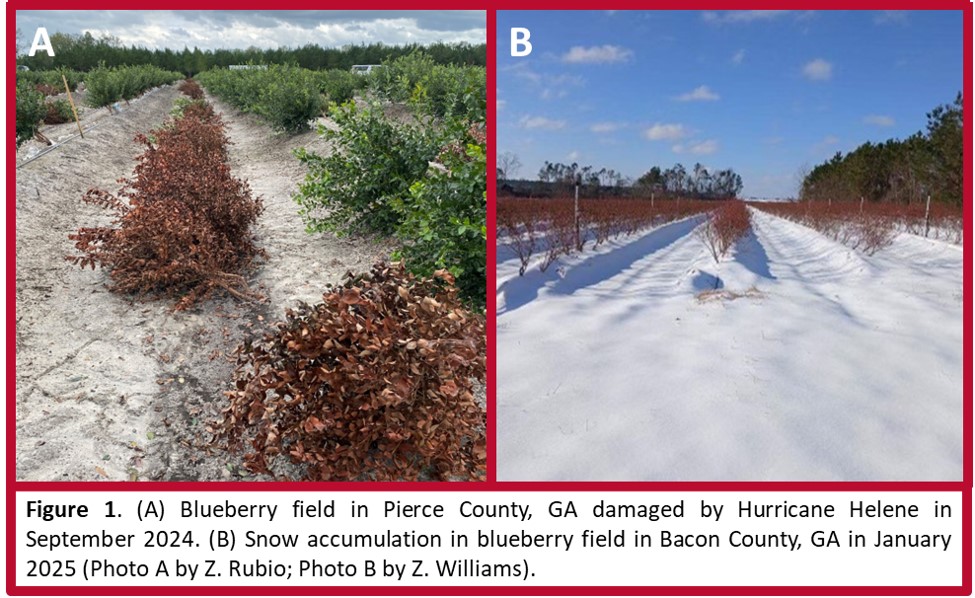

Blueberry plants in southern Georgia have faced numerous unusual environmental (weather) stresses over the past year. On September 27th, 2024, Hurricane Helene moved through Georgia and caused widespread damage (Figure 1A). During this event, blueberry plants at some locations in southern Georgia sustained significant damage due to wind and rain, with some plants being blown over (uprooted) and others being wind-whipped and defoliated prematurely. In late January 2025, a winter storm resulted in unprecedented snowfall even in extreme southern Georgia and snow remained on the ground for several days (Figure 1B). Thereafter, erratic fluctuations in temperatures and rainfall were noted during flowering, pollination, and fruit set this year. These combined stressors have had multifaceted impacts on plant growth stages across the region, potentially disrupting normal plant development in many locations.

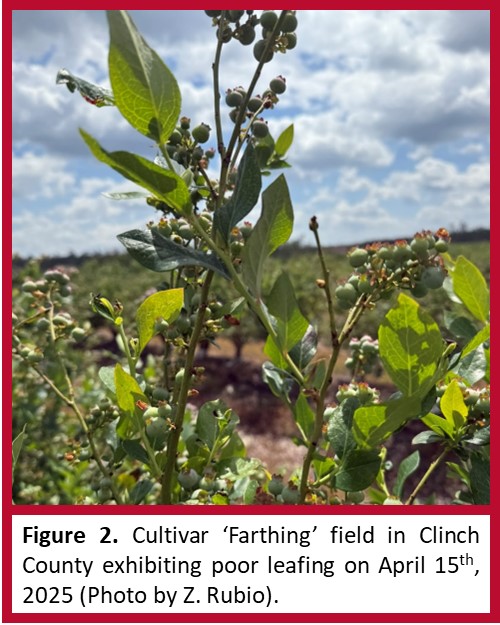

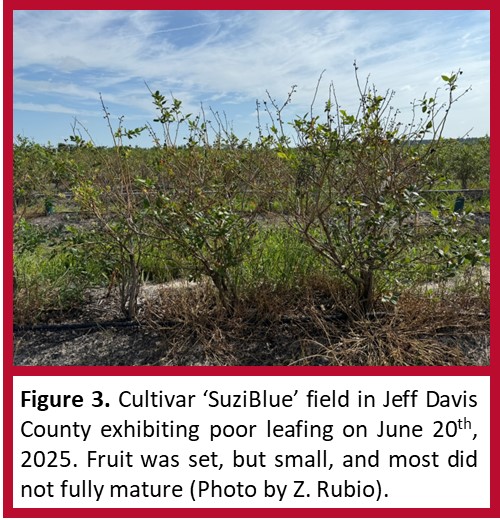

Among other issues observed during this growing season, plants with poor leafing have been reported in some locations within the blueberry-producing counties in southern Georgia. Early in the spring, affected plants were noted to have relatively few fully expanded/developed leaves relative to the large numbers of flowers present on these plants. As the fruit developed from these blooms, plants were noted to be “loaded-up” with fruit but still appeared to lag behind in leaf development as the season progressed towards harvest. In some cases, as fruit ripened and matured, it was observed that a large number of fruit remained red or green and failed to fully ripen when expected. The occurrence and prevalence of this appeared to vary from location to location and especially among different blueberry cultivars. For example, in some ‘Farthing’ plantings (Figure 2), numerous plants exhibiting this issue were noted, with relatively poor leafing relative to other nearby plants even within the same row/stand. Late in the harvest season, these poorly leafed out plants could be observed to have larger numbers of unripened fruit relative to other plants in the same location, which seemed to have comparatively more consistent leafing and more consistent ripening. In some ‘SuziBlue’ plantings (Figure 3), the issue was even more pronounced, with some entire fields showing very poor leafing. In these fields, even though large numbers of blooms (and, subsequently, fruit) were noted, much of the fruit on these plants failed to ripen in a timely manner and could not be harvested as a result.

Blueberry Leaf and Flower Bud Development

Blueberry plants develop two distinct types of buds: leaf (vegetative) buds and flower buds (Rubio Ames 2024 – UGA Extension Circular 1293). In the spring, leaf buds result in leaf growth, and flower buds develop into blooms. In so-called “low-” and “medium-chill” cultivars (which require 150-800 chill hours before breaking dormancy), the flower budbreak typically precedes the development and emergence of leaves from leaf buds. In a typical situation, leaf buds break shortly thereafter, and these photosynthetic factories (leaves) produce the energy necessary for the plant to ripen the developing fruit. The timing of leaf and flower budbreak (when leaves begin to emerge from leaf buds and blooms begin to develop from flower buds) is influenced somewhat by plant health and nutrition but the primary determinants are environmental cues, including chill hours. Of note, it has been observed that the different types of buds (leaf vs. flower) have different chilling requirements for emerging from dormancy. In most years and situations, these differences are ultimately negligible, and leaf and flower buds will develop into leaves and flowers, respectively, in a balanced manner that will lead to plants having normal leafing and fruit set (leaf to fruit ratio), respectively (which will then lead to typical growth and development of fruit). However, in some situations, things can get out of balance, and this can lead to issues.

Potential Causes and Implications of Imbalanced Development

Previous observations and research have shown that in many blueberry cultivars, leaf buds often develop faster at lower temperatures than flower buds; however, once chilling hour requirements have been met, and if higher temperatures occur around bud break, flower buds can break first and then can begin to develop much more rapidly than leaf buds (Mainland 1985; Lyrene 2004). In addition, flower bud development (and subsequent fruit development) can inhibit leaf buds from breaking dormancy and reduce vegetative growth (Mainland 1985; Lyrene 2004). This has been speculated to occur as a result of plant hormones produced by the developing flowers and fruit that inhibit leaf development to some extent (Mainland 1985). While some degree of inhibition is okay, and ultimately allows the plant to use its energy to maximize flower bud emergence and fruit set, if too much inhibition occurs due to an overabundance of flowers being produced and fruit being set, the plant can end up with insufficient leaves to ripen the developing crop. This tendency has been noted in both highbush and rabbiteye blueberries, but has been reported to be especially problematic in certain southern highbush cultivars. Early on in the production of highbush cultivars in North Carolina (Mainland 1985), “inadequate leaf surface [area]” was noted even in some years where plants received adequate chill hours overall. Drought, inadequate pruning, and heavy bloom and fruit set were noted to make the problem more severe, but the most critical factor was determined to be the occurrence of high temperatures during bud break (Mainland 1985). Likewise in northern Florida, some of the early southern highbush cultivars were especially noted to have a strong tendency to overcrop and have trouble producing new leaves in the early spring due to the inhibition of leafing by flower buds. With rising temperatures, a heavy crop load, and reduced carbohydrates (due to having few leaves), berries on these cultivars were noted to be small, delayed in ripening, and have reduced fruit quality (Lyrene 2004).

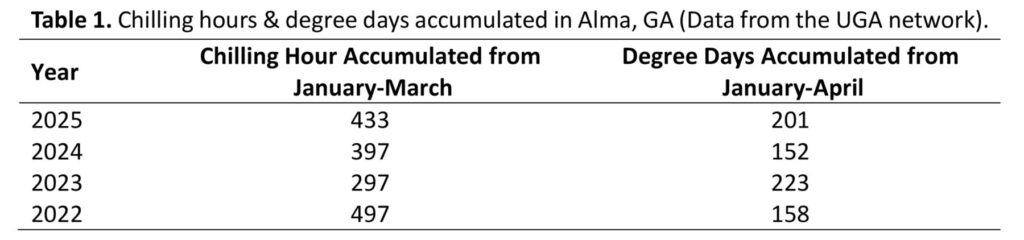

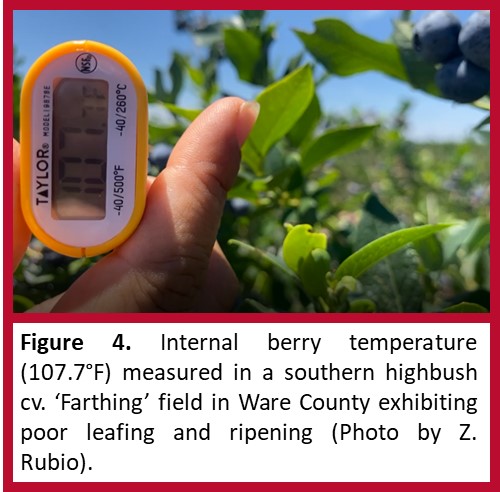

This season (from January to April) in Alma, Georgia, in the southern part of the state, a total of 434 chilling hours were accumulated from January to March, and from January to April, 201 growing degree days were recorded (Table 1). This fulfilled the chilling requirement and allowed for budbreak to occur. However, erratic temperature fluctuations, including unseasonably high temperatures early in the season were also noted, potentially leading to the flower buds breaking dormancy and outpacing (and inhibiting) the growth and breaking of vegetative buds in some cases – especially in plants with higher bloom and fruit set, inadequate pruning, and/or inadequate irrigation (drought exposure). The poor leafing observations reported earlier in the season (Figures 3 & 4), appear to be consistent with this – as some plants were observed to have poor leaf coverage into and past the harvest period (May and June) despite a substantial number of fruit being present. Leaves produce the carbohydrates necessary during the ripening process and function to cool the plant through transpiration and shading. If ambient temperatures reach over 90°F and plants do not have adequate leaf coverage to cool the plant and shade the fruit, both the plant and berries can overheat with the internal temperature of sun-exposed berries potentially reaching well over 100°F (Figure 4).

Final Thoughts and Suggestions

As erratic weather events become seemingly more common, these have the potential to reduce both yields and profits for blueberry growers. Thus, management practices should be tailored to reduce the impact of weather stressors. Pruning practices can lead to healthier and more balanced plants by reducing the flower bud load (and subsequent crop load), while maintaining yields through the production of larger, higher quality fruit on healthier more robust canes (Rubio Ames 2025). In addition to pruning practices, chemical thinning and vegetative growth acceleration may also be of benefit in some cases. Anecdotal observations during the current growing season suggest that where growers utilized the plant growth regulator, hydrogen cyanamide (Dormex®), plants exhibited better leafing and had fewer ripening issues. This observation matches with previous findings, which indicated that hydrogen cyanamide has both a thinning effect on flower buds (reducing crop load) while simultaneously increasing both vegetative bud break and yields in southern highbush cultivars (Buck et al. 2023).

References

Buck, J., Nunez, G.H., Munoz, P.R., and Williamson, J.G. 2023. Hydrogen cyanamide application accelerates vegetative bud break and causes earlier yield in ‘Optimus’ and ‘Colossus’ southern highbush blueberry. HortScience. 58(9):1049-1054.

Lyrene, P.M. 2004. Flowering and leafing of low-chill blueberries in Florida. Small Fruits Review. 3:3-4, 375-379.

Mainland, C.M. 1985. Some problems with blueberry leafing, flowering, and fruiting in a warm climate. Acta Horticulture – Vaccinium Culture. 165: 29-34.

Rubio Ames, Z. 2024. Recognizing flower and vegetative buds in blueberries: blueberry phenology. UGA Cooperative Extension Circular 1293. https://extension.uga.edu/publications/detail.html?number=C1293&title=recognizing-flower-and-vegetative-buds-in-blueberries-blueberry-phenology

Rubio Ames, Z., Rossi, F., Espinoza, N., and Faulk, M. 2025. Selective hand pruning does not reduce yield of ‘Farthing’ (Vaccinium corymbosum interspecific hybrids). Journal of the American Pomological Society. 79(2): 21-37. https://doi.org/10.71318/jd8cfr52