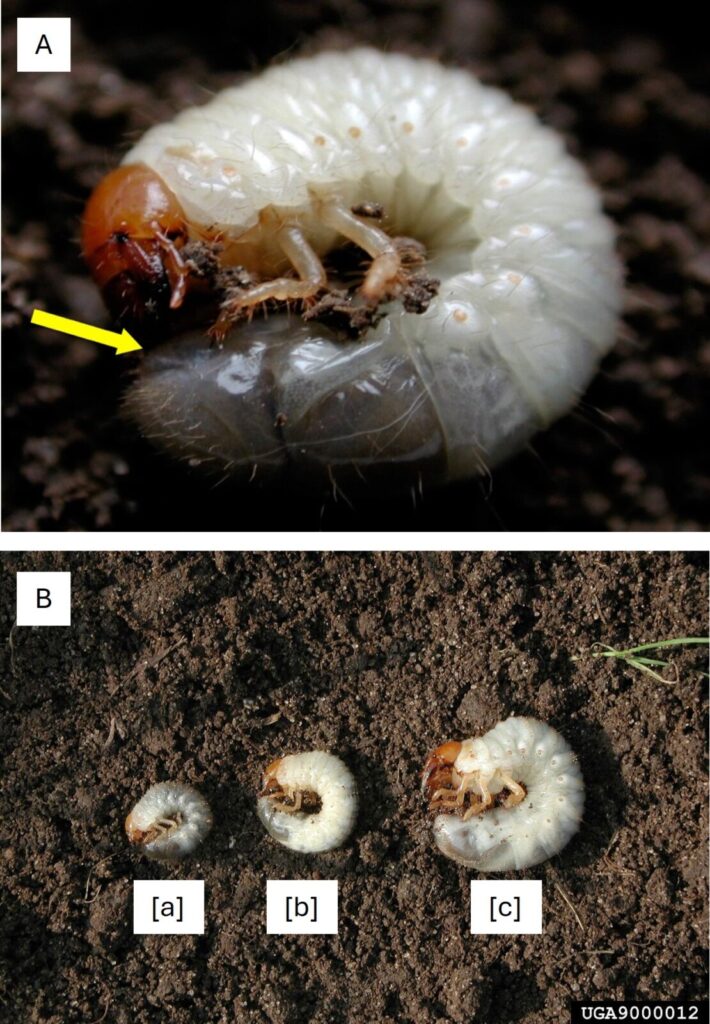

White grubs (Figure 1) are among the most destructive insect pests of turfgrass in Georgia and throughout the southeastern United States. These pests are the larval stages of several scarab beetle species, including Japanese beetles, green June beetles, and masked chafers (Figure 2). Grubs live in the soil and feed on turfgrass roots, causing patches of yellowing leaves. Over time, affected turf becomes wilted and may die under severe infestations. Because this damage often resembles drought stress, grub problems can go unnoticed. To confirm a white grub infestation, cut and lift the affected turf. If grubs are present, you will find multiple larvae beneath the sod or on the soil surface (Figure 3).

In Georgia’s warm climate, white grubs are a recurring problem in home lawns and professional turfgrass settings such as golf courses, sod farms, and athletic fields. Their impact extends beyond root damage as heavy infestations attract vertebrates like raccoons, skunks, armadillos, and even wild hogs, which dig up turf in search of larvae. Depending on the animal, this can result in anything from small holes (Figure 4) to large patches of destroyed turf.

Successful management requires understanding the grub life cycle, the conditions that favor their development, and the optimal timing for control measures. This article will provide an overview of common white grub species in Georgia, symptoms of grub damage, and effective strategies to protect your turfgrass.

General biology of white grubs

White grubs are the larval stage of scarab beetles (Family Scarabaeidae), a large and diverse group of insects found worldwide. These grubs are typically “C”-shaped, creamy white with a dark brown head capsule, and possess three pairs of well-developed legs near the front of the body (Figure 1). They live in the soil and feed on roots and organic matter, making them strong and highly destructive to turfgrass.

Adult scarab beetles vary widely in size and appearance. Some species are small, inconspicuous brown or black beetles, while others are larger and brightly colored with metallic green, blue, or yellow hues. Many species are nocturnal and often go unnoticed except when attracted to outdoor lights at night. Depending on the species, the beetle life cycle may take one to three years to complete.

White grubs progress through three larval stages (instars) before pupating in the soil and emerging as adult beetles. The larval stages are the most damaging to turfgrass because grubs feed on grass roots in the upper soil layer. This feeding weakens turf, reducing its ability to absorb water and nutrients, and can lead to large dead patches, especially during hot or dry periods.

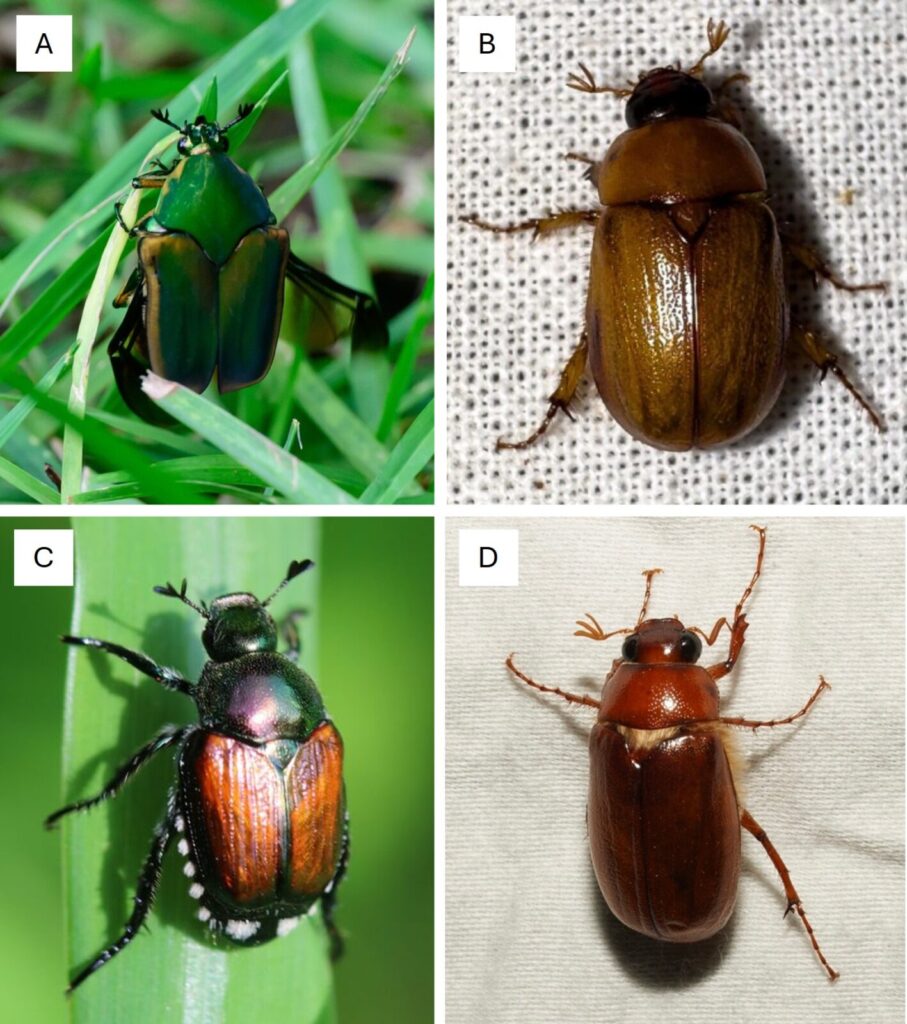

Members of the scarab family are significant pests not only of turf and pasture grasses but also of row crops, ornamentals, and forest or shade trees. Damage occurs in both life stages: adults may defoliate plants by feeding on leaves, while larvae cause below-ground injury by destroying roots. Infestations in turfgrass often involve multiple scarab species (Figure 2), making identification and management more challenging. Their nocturnal adult habits and the hidden nature of grubs in soil further complicate detection and monitoring until visible damage appears.

Adult scarab beetles range from 1/8 inch to over 1 inch in length. While many are inconspicuous brown or black, some species exhibit bright metallic colors such as green, blue, or yellow. Most are sluggish and rarely seen except when attracted to lights, where they may be found dead beneath light sources.

Distribution in Georgia

Notable species in Georgia include the Japanese beetle (Popillia japonica), green June beetle (Cotinis nitida), May and June beetles (Phyllophaga spp.), and masked chafers (Cyclocephala spp.). These grubs are distributed statewide, thriving in environments where adult beetles can access turfgrass to lay eggs during the summer months.

Life cycle

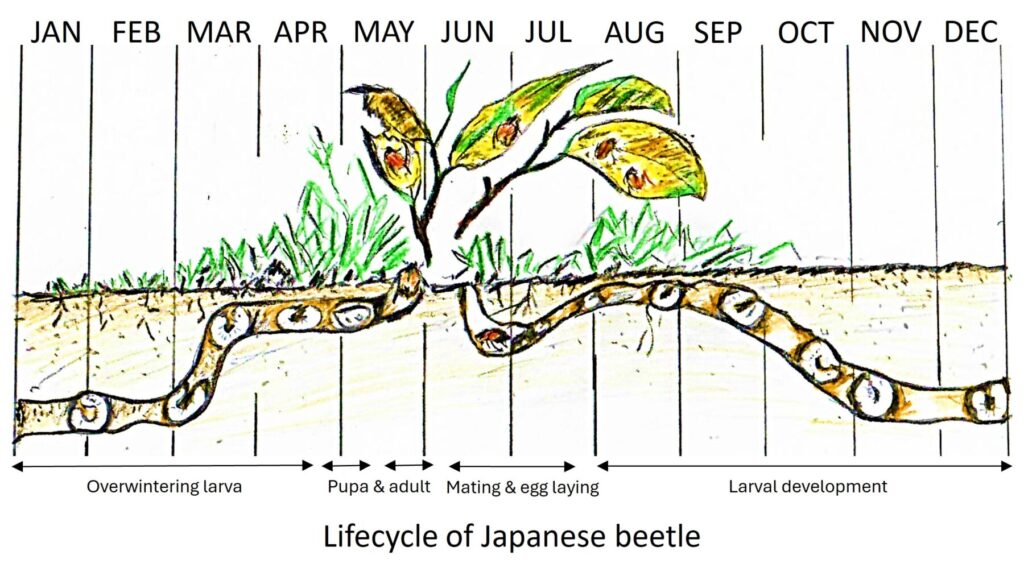

While each species has unique features, their general life cycle follows a similar pattern with important seasonal timing. An example of the Japanese beetle life cycle is shown in Figure 5.

Egg Stage (Summer):

Adult beetles emerge from late spring to early summer and lay eggs in turfgrass soil, typically in sunny, moist areas. Egg-laying generally occurs from June through August, depending on species and weather conditions.

Larval Stage (Late Summer to Fall):

Eggs hatch within 1–2 weeks, and young larvae begin feeding on turfgrass roots. This is the most damaging stage, as grubs grow rapidly through three instars from August to October. Turfgrass often shows signs of thinning, yellowing, or wilting during this period.

Overwintering (Winter):

As soil temperatures drop in late fall, grubs migrate deeper into the soil (4–8 inches) to overwinter. Turf damage becomes less noticeable, but infestations persist below the surface.

Spring Activity (March–May):

As soil temperatures warm, grubs move back toward the root zone and resume feeding briefly before pupating. This spring feeding can cause additional turf stress, though typically less severe than fall damage.

Adult Emergence (Late Spring):

Mature larvae pupate in the soil and emerge as adult beetles in late spring or early summer, completing the cycle. In Georgia, most turf-infesting white grub species complete their life cycle in one year, while a few species—such as May and June beetles—may take up to three years.

Identification

White grub identification relies on a combination of visible morphological and taxonomic features, particularly the raster pattern (arrangement of spines at the tip of the abdomen) and relative leg size. The raster pattern is a key diagnostic characteristic and often requires magnification, such as a hand lens or microscope, for accurate observation.

Key Taxonomic Features of Major Species

Green June Beetle (Cotinis nitida)

- Larvae: Easily recognized by their relatively small legs compared to their large body size. They exhibit a unique behavior: crawling on their backs with their legs held upward. The raster consists of two irregular, parallel rows of spines resembling a zipper or dense cluster (Figure 6).

- Adults: Large beetles (~1 inch), metallic green with bronze to yellow wing margins (Figure 2A). Active fliers in midsummer, often buzzing loudly over turf. Adults feed on ripe fruits and ornamentals; larvae feed on organic matter and roots in rich, moist soils.

Masked Chafers (Cyclocephala lurida and related species)

- Larvae: Raster spines scattered randomly across the posterior end, not arranged in rows (Figure 6). Full-grown larvae measure about 1 inch and are found in the top 2–3 inches of soil.

- Adults: Light tan to golden-brown, oval-shaped beetles (~½ inch) with a slightly darker head and thorax (Figure 2B). Nocturnal and strongly attracted to lights in summer. Adults feed minimally; larvae are serious turf pests, causing wilting and dead patches.

Japanese Beetle (Popillia japonica)

- Larvae: Raster pattern forms a distinct “V” shape of converging rows (Figure 6). Commonly found in the top 1–2 inches of soil.

- Adults: Smaller than June beetles (~3/8 inch), metallic green head and thorax, coppery-brown wing covers, and white hair tufts along each side of the abdomen (Figure 2C). Active during the day, feeding on foliage, flowers, and fruits of over 300 plant species, skeletonizing leaves, and damaging ornamentals and turf.

May or June Beetles (Phyllophaga spp.)

- Larvae: Raster spines arranged in two distinct parallel rows (Figure 6). Typically found deeper in the soil (3–4 inches).

- Adults: Medium to large brown beetles (½–1 inch), robust oval body with a dull, velvety appearance (Figure 2D). Strongly attracted to lights at night in spring and early summer. Adults feed on tree and shrub foliage; larvae are among the most damaging white grubs in turf and pasture because of their deep-root feeding.

Damage symptoms

In turfgrass (lawns and sod), white grub damage typically begins with gradual thinning, yellowing, and browning of the grass, eventually forming irregular dead patches despite adequate soil moisture. Upon inspection, the sod often feels spongy and lifts easily from the soil like a carpet because grub feeding has destroyed the roots. Grubs are usually visible beneath the turf (Figure 3). These larvae not only sever roots but can prune them so severely that the turf loses nearly all anchorage. Additional signs of grub activity include increased foraging by raccoons, moles, or birds that dig up the lawn in search of larvae, as well as burrow mounds created by green June beetles as they move through the soil.

Management

White grub management relies on an integrated approach that combines cultural, physical, chemical, and biological control strategies to minimize damage and reduce pest populations.

Cultural Control

Maintain healthy, well-drained turf and crops to discourage egg-laying and rapid grub development. Avoid overwatering, as excessive moisture creates ideal conditions for grubs, which prefer soft, moist soils and avoid dry, compacted ground. Implement crop rotation and avoid planting highly susceptible crops (such as turf or sod) in the same field year after year. Proper fertilization and mowing encourage vigorous root growth, enabling turf to tolerate minor infestations. Although no turfgrass is completely resistant, warm-season grasses such as bermudagrass generally exhibit greater tolerance to white grub damage than cool-season species such as Kentucky bluegrass and ryegrass, which are more susceptible. Tall fescue also shows relatively higher tolerance due to its extensive root system, which can withstand more feeding before significant damage occurs.

Physical Control

Physical control methods primarily involve practices that directly reduce grub populations or create conditions unfavorable for their survival. Regular manual scouting and soil inspection—such as cutting and lifting sections of sod to sample for grubs—are essential for early detection and accurate population assessment, enabling targeted intervention only when densities exceed damaging thresholds. Deep tillage or plowing in early fall or late spring can kill larvae and pupae in the soil while exposing them to natural predators such as birds and beneficial insects, thereby significantly reducing populations in agricultural settings. In turfgrass, practices such as dethatching, core aeration, and removing dense organic layers not only make the soil less suitable for egg-laying but also decrease moisture retention, which grubs favor.

Biological Control

Entomopathogenic Nematodes (Heterorhabditis bacteriophora, Steinernema glaseri): These nematodes are most effective against young grubs when applied to moist soil, ideally in late summer. Their populations require time to establish before providing significant suppression. Because they have a limited shelf life, they should be applied during the same season they are purchased, with earlier applications generally yielding better results. Application can be made using a sprayer at a dilution of 1.5–2 gallons of water per 1,000 square feet. To maximize effectiveness, apply in the late afternoon to reduce UV exposure, then irrigate immediately and continue watering for several days to maintain soil moisture.

Entomopathogenic Fungi (Beauveria bassiana, Metarhizium anisopliae): Commercial formulations are available for long-term suppression of grub populations.

Bacillus thuringiensis galleriae (Btg): A bacterial insecticide that targets Japanese beetles, providing control of both adult beetles and larval stages.

Conserving natural enemies: Many birds, predatory beetles, and other beneficial organisms suppress grubs and should be protected as part of an integrated management strategy.

Chemical Control

Chemical control remains the most reliable option for managing white grubs in high-value turfgrass such as golf courses, athletic fields, and sod farms, provided applications are properly timed and executed. Preventive insecticides are most effective when applied in early to mid-summer (June–July in Georgia) as eggs hatch and larvae are small and most susceptible. Common preventive products include the neonicotinoids imidacloprid, thiamethoxam, and clothianidin, as well as the diamide chlorantraniliprole, which offers extended residual activity and can be applied earlier in the season (May–June). Tetraniliprole, registered for turfgrass use only in and around residential, commercial, and institutional buildings, golf courses, and sports fields, is also effective against white grubs.

Curative insecticides are used later in the season (August–October) when larger larvae are actively feeding, and visible turf damage occurs. Products such as carbaryl (Sevin®) and trichlorfon (Dylox®) provide rapid knockdown of older larvae but have shorter residual activity compared to preventive options. Regardless of the product, thorough irrigation with 0.5–1 inch of water immediately after application is essential to move the active ingredient into the root zone where grubs feed.

Chemical treatments should be applied only when grub populations exceed economic thresholds determined through scouting, and insecticide classes should be rotated annually to reduce the risk of resistance. When properly timed and applied, chemical control is an effective component of an integrated management program for white grubs in Georgia turfgrass.

References

Brandenburg, R. L., & Villani, M. G. (1995). Handbook of Turfgrass Insect Pests. Entomological Society of America, Lanham, MD.

November 5, 2016 | New Mexico State University | BE BOLD. Shape the Future. (2016). Nmsu.edu. https://swyg.nmsu.edu/2016/110516.html

Potter, D. A., & Braman, S. K. (1991). Ecology and Management of Turfgrass Insects. Annual Review of Entomology, 36(1), 383–406. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.en.36.010191.002123

Potter, D. A. (1998). Destructive Turfgrass Insects: Biology, Diagnosis, and Control. Chelsea, MI: Ann Arbor Press.

Potter, D. A., Redmond, C. T., & Scharf, M. E. (2005). Managing the white grub complex on golf courses and landscapes. Pest Management Science, 61(8), 801–807.

Purdue Extension Entomology. (2023). Managing White Grubs In Turfgrass. Purdue.edu. https://extension.entm.purdue.edu/publications/E-271/E-271.html

Richmond, D. S., & Shetlar, D. J. (2005). Control of white grubs in turfgrass. The Ohio State University Extension Bulletin L-15-05.

Tashiro, H. (1987). Turfgrass Insects of the United States and Canada. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

White Grub Control in Turfgrass. (2025). Wisconsin Horticulture. https://hort.extension.wisc.edu/articles/grub-control-home-lawn/

White Grub Management on Lawns | University of Maryland Extension. (2023). Umd.edu; University of Maryland Extension. https://extension.umd.edu/resource/white-grub-management-lawns/

White Grubs in Turf | NC State Extension Publications. (2016). Ncsu.edu. https://content.ces.ncsu.edu/white-grubs-in-turf