“Fruit flies” in the genus Drosophila are widely known for their association with rotting fruit and vegetation, but they actually derive much of their nutrients from microbes growing on these rotting substrates. In close relatives of fruit flies, however, a remarkable transition has occurred multiple times independently: flies have evolved to consume living plant tissue! To make this transition, these flies had to overcome the challenges to feeding on a new diet — including exposure to high levels of defensive toxins that plants produce to defend themselves against herbivores. We study these flies to understand how herbivory evolves.

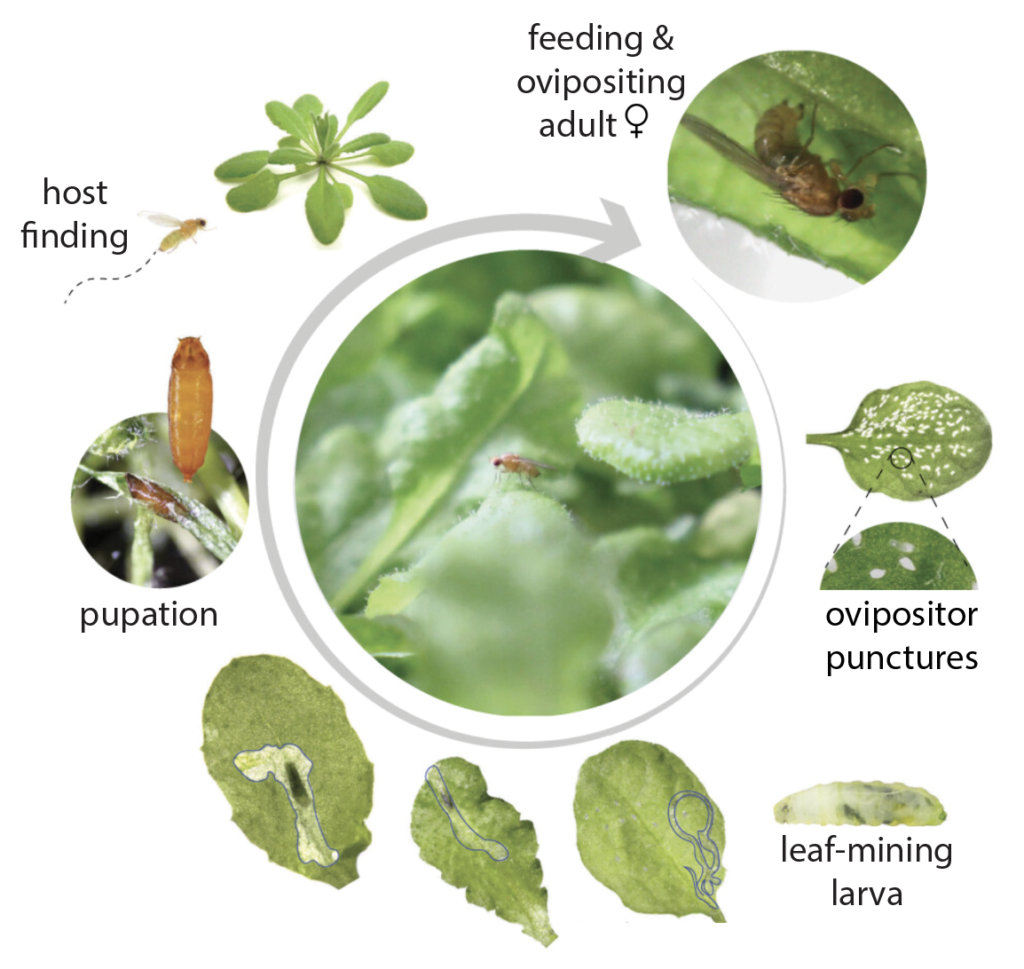

The life cycle of these herbivorous flies is intimately tied to their host plants. Adult flies mate on or near a host plant. After mating, adult females use a cutting ovipositor to wound leaves, and they consume the juices that flow from these wounds. They also deposit eggs into these wounds. Larvae hatch from these eggs into the interior of the leaf, where they consume leaf tissue as “leafminers”. Finally, pupation occurs on or near the leaves. When an adult fly emerges, the cycle begins again. In a sense, these flies are not only herbivores, but also parasitoids of plants! The life cycle of one species, Scaptomyza flava, is shown below.

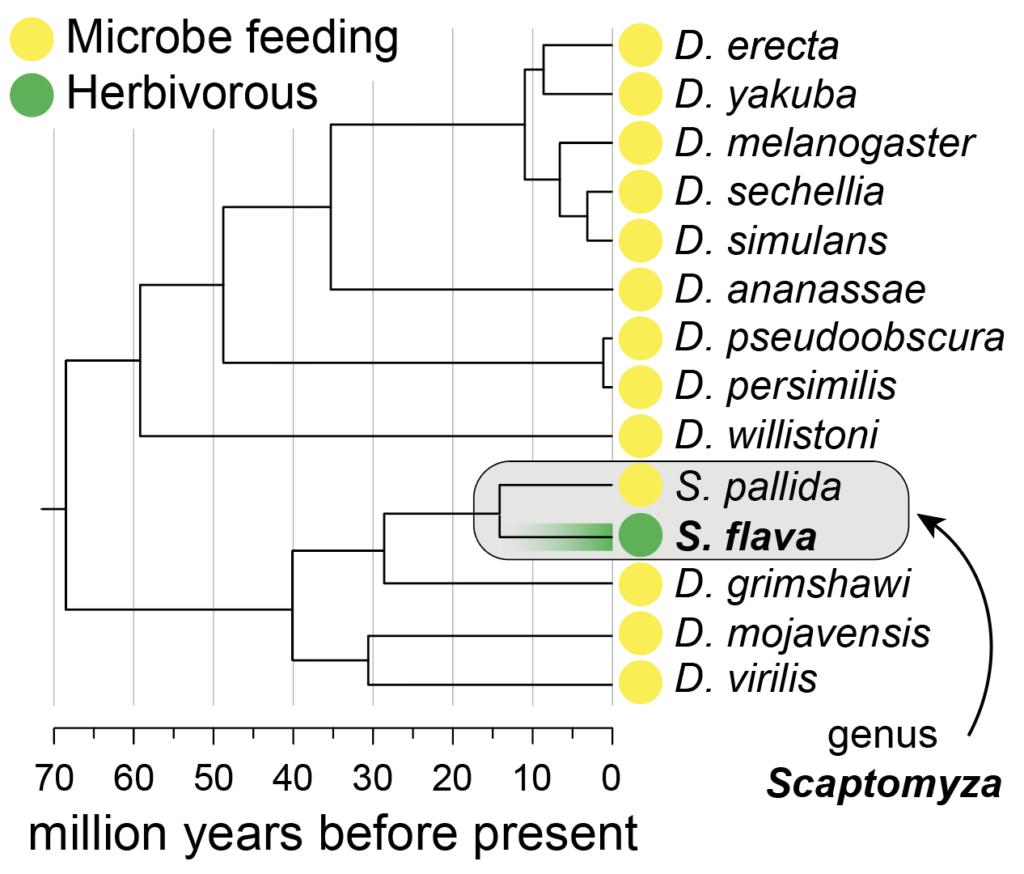

Herbivorous Scaptomyza are nested phylogenetically within the genus Drosophila, composed largely of flies that consume microbes present on rotting fruit and plant material, as illustrated below. This makes studying the shift to feeding on living plant tissue in Scaptomyza highly tractable: we can compare genomes between Scaptomyza and hundreds of Drosophila to confidently identify genes with changes unique to herbivorous lineages, apply the wealth of experimental data from the Drosophila research community to inform hypotheses of how these genes function, and use the vast genetic toolkit for Drosophila to experimentally characterize how the functions of these genes adaptively evolved to facilitate herbivory.

The genetic underpinnings of many physiological and ecological processes, including those related to diet and nutrition, are better understood in Drosophila than in any other insect. This offers an exceptionally powerful foundation for illuminating how herbivory evolves, from genes and genomes to biochemistry to physiology to organismal traits.

To learn more about herbivorous Scaptomyza flies, and see up-close photos and images of how they attack plants, check out the following links: